San Francisco Ascendant. Again.

TL;DR: San Francisco is back. Not “recovering” back — thunderously, undeniably back. AI has reignited the city with an unmistakable energy. But the real story isn’t AI itself — it’s why SF keeps reinventing itself when other tech hubs flame out. I believe the answer is a 152-year-old California law that most people have never heard of.

The Original Silicon Valley

Let’s start with what people forget: Silicon Valley wasn't San Francisco.

The Valley — the actual, original Valley — was orchards. Apricots, cherries, and plums stretching across the Santa Clara Valley floor from San Jose to Palo Alto. The transformation started at Stanford, where Frederick Terman encouraged his students to start companies nearby instead of fleeing east. Two of those students, Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard, started tinkering in a garage in Palo Alto in 1939. That garage is now a California Historical Landmark. It should be a national one.

Then came William Shockley. Nobel laureate. Coinventor of the transistor. World-class asshole. He set up Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory in Mountain View in 1956, recruiting the best young minds he could find. The problem? He was a terrible manager and, increasingly, a terrible human being. So in 1957, eight of his brightest engineers — the Traitorous Eight — walked out and founded Fairchild Semiconductor.

This is the Big Bang of Silicon Valley. Not a metaphor. Literally the moment.

From Fairchild came Intel (Gordon Moore and Robert Noyce, 1968). From Fairchild and its offspring came AMD, National Semiconductor, and dozens of other companies — the so-called “Fairchildren.” The name “Silicon Valley” itself came from journalist Don Hoefler in 1971, describing the silicon chip manufacturers clustered in the South Bay.

All of this — HP, Fairchild, Intel, AMD — happened in Palo Alto, Mountain View, Santa Clara, San Jose, Menlo Park. The South Bay. San Francisco, 40 miles north, was doing its own thing: beats, hippies, the Summer of Love, banking, and shipping. Tech? That was down the peninsula.

For decades, that’s how it stayed.

The Northward Migration

Around 2001, Voxeo — the voice platform company I started with a great team — acquired a small startup called Milo. They were based in San Francisco. “What the heck are they doing in San Francisco?” we asked. Tech companies weren’t in San Francisco. Not that we had solid silicon ground beneath our own feet — Voxeo was based in Scotts Valley, up in the Santa Cruz mountains. Both offices were extreme outliers. But looking back, Milo was a canary. Within a decade, SF wouldn’t be the outlier — it would be the center of everything.

The conceptual "Silicon Pole" marking the center of Silicon Valley started quickly moving north around 2010.

Young engineers didn’t want to live in Cupertino. They didn’t want to drive to a corporate campus surrounded by parking lots. They wanted to walk to bars, eat interesting food, and live in a city that felt alive. San Francisco had all of that.

The city leaned in. In 2011, Mayor Ed Lee pushed through the now-famous “Twitter tax break” — a payroll tax exclusion for companies that moved to the blighted Mid-Market corridor. Twitter relocated from the South Bay to the old San Francisco Furniture Mart on Market Street. Zendesk, Square, Uber, and dozens of startups followed.

The cool factor was real. YC companies that would have set up in Mountain View started choosing SF. Seed rounds closed in coffee shops in SoMa. The Mission became tech’s living room. For the first time in the Valley’s history, the center of innovation wasn’t in the Valley at all — it was in the city.

The South Bay didn’t die, of course. Apple built its spaceship. Google kept expanding. But the energy, the startup energy, the “we’re building the future. energy — that moved to San Francisco.

Around 2018 things started to shift again. Zoom was... zooming. Work from home was booming. We had an office and residence in Tiburon, a short and beautiful ferry ride from SF. We sold it and returned to Florida.

The COVID Exodus

Then 2020 happened, and it San Francisco fell apart.

Remote work didn’t just empty offices — it broke the premise of San Francisco. If you didn’t need to be near your coworkers, why would you pay $3,500/month for a one-bedroom in SoMa? Why would your company pay $85/sqft when they could pay $35 in Austin?

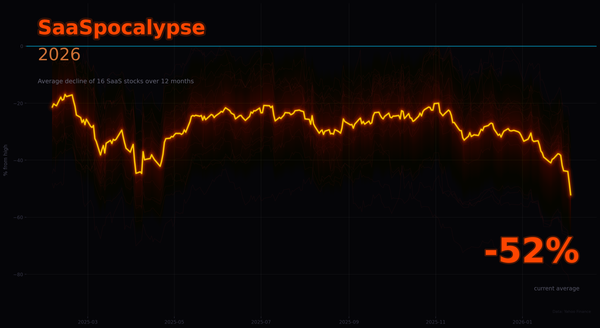

The exodus was real and it was brutal. Oracle moved to Austin. HP Enterprise moved to Houston. Palantir moved to Denver. Even Elon Musk eventually pulled X (née Twitter) out of the very building that the tax break had lured it into — the ultimate middle finger to the city.

Tech workers scattered. Miami had its moment. Austin had its moment. Everyone had a hot take about SF being finished.

Downtown office vacancy spiked past 30%. The “doom loop” narrative took hold: empty offices → less tax revenue → fewer services → more people leave → more empty offices. Walking through the Financial District in 2021 felt post-apocalyptic. Plenty of smart people wrote San Francisco’s obituary. And honestly? I agreed.

The AI Renaissance

They were wrong.

I just spent a week in San Francisco and holy $&(@ — the energy is palpable. Not in the Financial District (still rough). Not on Market Street (getting better). But in SoMa, the Mission, Potrero Hill, Dogpatch, and Mission Bay — the area locals are calling “The Arena” — it feels like 2012 again. Maybe better. I met geniuses and visionaries; Facebook founders; and friends new and old.

Why? AI chose SF.

OpenAI is in the Mission District. Anthropic keeps expanding — they just signed a $111 million office deal for additional space, on top of their already massive footprint. Scale AI, Databricks, Mistral’s US office, Cohere, Character.AI — they’re all here. Mission Local literally built an interactive map of all the AI companies clustered in a handful of SF neighborhoods.

The numbers are staggering. AI companies have absorbed millions of square feet of office space in the city. Mission Bay’s vacancy rate is down to 9.1% — while the rest of downtown sits at 30%+. Over $100 billion in VC funding has flowed to SF-based AI startups since 2024. The NYT called it a “new gold rush,” and for once, the mainstream media isn’t exaggerating. AI is going to change ev...ery...thing. In fact it already has, it's just that most people (and companies) haven't felt it yet.

What struck me most during my week there wasn’t the office buildouts or the funding numbers. It was the people. Random 20-somethings arguing about transformer architectures at coffee shops. Neck-beards covering white-boards with flow-blocks. Figurative hiring signs everywhere. The unmistakable buzz of a place where people know they’re building something that matters.

Not in Palo Alto. Not in San Jose. Not in Austin or Miami or New York. In San Francisco.

The Secret Sauce

OK, so AI chose SF. But why? Why does the Bay Area keep regenerating when other tech hubs peak and fade?

The standard answers — Stanford, VC density, network effects, weather — are all true but incomplete. Lots of places have good universities and nice weather. Boston has MIT and Harvard. Austin has cheap rent and no state income tax. New York has more capital than God.

The real answer is California Business & Professions Code §16600. It’s been on the books since 1872 and it says, in essence: non-compete agreements are void and unenforceable in California.

This is not a minor legal footnote. This is the engine of Silicon Valley innovation, and it has been since the beginning.

Think about the Traitorous Eight. In 1957, eight engineers walked out of Shockley Semiconductor and immediately started a competing company. In the same city. Making the same products. In most states, Shockley’s lawyers would have crushed them. Non-compete clauses would have locked them down for two, three, maybe five years. By the time they were free, the moment would have passed.

But this was California. So they walked out on a Friday and started Fairchild on a Monday. And from Fairchild came Intel. And from Intel came the microprocessor. And from the microprocessor came… everything.

“The most important law in Silicon Valley isn’t Moore’s Law. It’s §16600.”

AnnaLee Saxenian nailed this in her landmark 1994 book Regional Advantage. She studied why Silicon Valley thrived while Boston’s Route 128 — which had every advantage in the 1970s (MIT, Harvard, DEC, Wang, Raytheon, massive defense contracts) — declined into irrelevance. Her conclusion: Route 128’s culture was hierarchical and secretive. Companies enforced non-competes aggressively. Knowledge stayed locked inside corporate walls.

In Silicon Valley, engineers changed jobs constantly. They talked to each other at bars, at meetups, at kids’ soccer games. Ideas cross-pollinated. Failed startup engineers brought hard-won knowledge to the next venture. The talent pool was fluid, and that fluidity was the innovation engine.

The NYT called it Silicon Valley’s “secret sauce.” MIT Sloan research has confirmed what Saxenian argued: banning non-competes doesn’t just help individual workers — it accelerates innovation at a regional level.

Knowing its value, the FTC tried to ban non-competes nationally in 2024. A (dumbass) federal judge in Texas blocked it. Which means California still has its structural advantage. If you’re a brilliant AI researcher at Google DeepMind and you want to leave and start your own company tomorrow, you can — if you’re in California. If you’re at a research lab in Boston or New York, good luck with your 18-month non-compete.

This isn’t just theory. It’s playing out right now, in real time. AI talent is churning through SF companies at an extraordinary rate. Researchers leave OpenAI and start Anthropic. Engineers leave Google Brain and join startups. The cross-pollination that powered Fairchild’s children in the 1960s is powering AI’s explosion today.

Why This Matters

I’ve been in tech long enough to have a career arc that reads like alphabet soup: 6502→Pascal→C→JS→CAC→MRR→LTV→NPS→ENPS→M&A→ROI→IRR→KISS→SAFE→LP→SPV→GO→AI. Through every cycle — PCs, internet, mobile, cloud, crypto, AI — the epicenter has always been somewhere in the Bay Area. But where in the Bay Area keeps shifting.

The South Bay built the hardware foundation. San Francisco captured the software and mobile era. COVID nearly killed it. AI brought it roaring back.

But the constant through all of it — the thing that makes the Bay Area the Bay Area — isn’t any single technology. It’s the freedom to leave, to start over, to take what you’ve learned and build something new. That freedom is encoded in California law, embedded in the culture, and reinforced by sixty-plus years of people doing exactly that.

San Francisco is the capital of innovation again. Not because AI is magic. Because the same structural forces that let eight angry engineers walk out of Shockley Semiconductor in 1957 are still at work today, in the same state, under the same law.

The orchards are long gone. The chips are fabbed in Taiwan now. But the engine — the human engine of talent moving freely, ideas spreading openly, and people betting on themselves — is still running.

It’s one hell of a thing to experience in person.

References

- NYT: “Insider’s Guide to San Francisco’s AI Boom” (Aug 2025)

- SF Chronicle: Anthropic Office Expansion

- SFGate: Anthropic $111M Office Deal

- SF Standard: AI Office Footprint (Jan 2026)

- CNBC: Ed Lee’s Twitter Tax Break

- WIRED: X Leaving San Francisco

- Vox: California Non-Competes (2017)

- NYT: California’s Non-Compete Secret Sauce

- UC Berkeley: Saxenian on Silicon Valley’s Secret Sauce

- MIT Sloan: Non-Compete Ban & Innovation

- Wikipedia: Traitorous Eight

- Wikipedia: Silicon Valley

- The Verge: Tech Exodus (2020)

- The Guardian: SF Tech Workers Leaving

- History Cooperative: History of Silicon Valley

- All About Circuits: Traitorous Eight & Fairchild

- Forbes: Fairchild & the Men Who Invented Silicon Valley

- SF Chronicle: “The Arena” in the Mission

- Mission Local: AI Company Map