People are People

TL;DR: A business can only compete on three things: People, Product, or Price. AI is killing product differentiation. Price competition is a death spiral. That leaves people—which really means customer service and trust. I’ve been obsessed with this my entire career. Three experiences tonight—two extraordinary, one catastrophic—reminded me why.

I’ve written before about the People-Product-Price framework. I’ve been using it for twenty years. I originally heard it from John Amein, who worked with me at Voxeo. Tonight the universe decided to give me a masterclass in both ends of the spectrum in a single night.

First, let me set the stage.

The Three-Legged Stool

Every business, in every industry, competes on some combination of three things:

- Product — What you sell

- Price — What you charge

- People — How you treat the humans who fund your paycheck

That’s it. There is no fourth option.

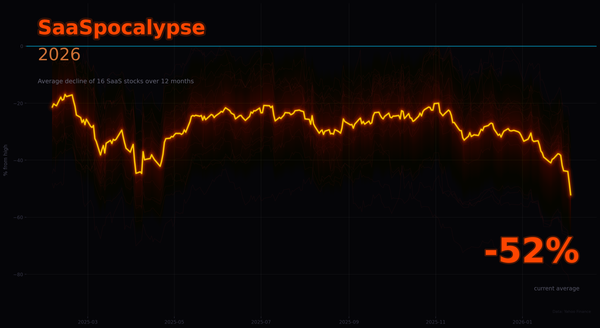

Competing on price is miserable. As I wrote in SaaS is Dying, there’s always someone willing to charge less, bleed longer, or give it away for free. Price competition is, as Michael Porter famously warned, “a race to the bottom that no one wins.”

Competing on product is increasingly futile. AI has commoditized software development. What took a team of ten eighteen months can be vibe-coded into existence in a weekend. Hardware differentiation is eroding. Even service delivery is being automated. Your product moat is melting.

That leaves people. And people is really about two things: customer service and trust.

Customer Obsession

I am obsessed with customer service. Genuinely, clinically obsessed.

At Voxeo, we were so obsessed that we coined the term “Customer Obsession” — and trademarked it. We meant it literally.

I used to tell the Voxeo team: “The only reason we have our software and services is so the customers don't think it's really weird that we keep trying to help them.”

That wasn’t a joke. It was our operating philosophy. The software existed to give us a reason to be in our customers’ lives. The real product was the relationship.

The result? Voxeo maintained a Net Promoter Score above 65. For context, the global average NPS is +32. According to Contentsquare, “a score of 60 or higher is generally a very good NPS in any industry.” SurveyMonkey’s benchmarks classify anything above 50 as “excellent.” We were excellent. In telecom. An industry not exactly known for making customers happy.

At PhotoDay, we took it even further. Our NPS hit 92%. Ninety-two. Chattermill calls anything above 80 “world-class.” For reference, Apple’s NPS hovers around 72, Netflix around 68, and Tesla around 97 (though that number is debated). A 92 puts you in genuinely rarefied air.

These numbers aren’t accidents. They’re the result of systematic, relentless prioritization of customer experience above almost everything else.

A Tale of Three Humans

Because of this obsession, I am magnetically drawn to great customer service — and viscerally repulsed by bad customer service. I notice it everywhere. I can’t turn it off.

This week gave me all extremes in a single night.

I’ve been on the road for almost three weeks straight. Mostly great experiences. citizenM continues to be brilliant — they’ve figured out that a hotel doesn’t need a massive lobby and a concierge desk to make you feel welcome; it needs a clean room, fast WiFi, and staff who actually smile. A hotel in Millbrae didn’t have my reserved room available, so they refunded my money and put me up at another hotel nearby. For free. No argument. No escalation. Just: “We messed up, let us make it right.”

That’s how it’s supposed to work.

Then came Houston.

Sydni, Enterprise, and George Bush Intercontinental

My flight landed at Houston’s George Bush Intercontinental at 1 AM. The problem: Enterprise at IAH closes at 1 AM.

I got on the rental car shuttle as fast as I could, but by the time I reached the rental car building it was 1:17 AM. The Enterprise desk was dark. Closed. I was about to pull up Uber when I decided to check the garage anyway — maybe there was a way to reach someone.

When I got to the top of the escalator, there was Sydni.

“I thought you’d be coming, so I sent everyone else home and I stayed.”

This was the second time I’d met Sydni. Three weeks earlier, on my first trip through Houston, she’d saved me by finding a key that was in the car but not anywhere I could locate it. Both times: happy, helpful, and a great problem solver.

Sydni is probably 21 years old. She gets it more than most executives I’ve worked with.

As Danny Meyer writes in Setting the Table: “Service is a monologue — we short to say how we should do things. Hospitality is a dialogue — we listen to how you feel about how we’re doing things.” Sydni doesn’t just provide service. She provides hospitality. She anticipated my needs before I articulated them.

This is what Depeche Mode was talking about. People are people. The best ones don’t need a manual.

Jason, Hilton, and Home2 Suites

After getting the car — thanks to Sydni — I made the drive from Houston to Webster and arrived at the Home2 Suites around 2:30 AM.

Jason was at the front desk. He looked dour, sour, and unhelpful.

And boy, was he.

“Your reservation was cancelled. You got here too late.”

I explained that my flight didn’t land until 1 AM. His response:

“That’s poor planning on your part, and not my problem.”

Now, some of you know I can have my own dour side. But buoyed by the string of good experiences I’d had over the past three weeks — the Millbrae hotel, citizenM, Sydni — I stayed calm.

Jason didn’t.

He escalated. “You look like someone who has never been told ‘no’ in your life.” Then: “If you don’t stop talking, I’m going to cancel your reservation.” He insisted my room wasn’t paid for. It was — I had the confirmation.

I had to call my colleague at 3 AM their time to get things sorted. And then Jason started being dishonest — with my colleague on the phone, and then with his own boss when I asked him to call management.

Here’s the thing Jason didn’t know: as soon as he said “not my problem,” I started recording from a phone in my vest pocket. I have the audio. The lobby cameras have video. Every word is documented.

He never asked me to leave — which, honestly, I wanted to do anyway. Instead, he said “watch this” and called the police.

I politely spoke with the officers and left.

Tony Hsieh, the late founder of Zappos, wrote: “Customer service shouldn’t just be a department, it should be the entire company.” Jason isn’t just a bad employee. Jason is a symptom of a company that has stopped caring about the humans who keep it alive.

Trust and Anti-Trust

In the morning, either Jason will be fired or his boss doesn’t care about dishonesty. Both outcomes are possible. Both are damning in different ways.

I’m infamous among friends and colleagues for banning vendors. When a company loses my trust, they lose my business — not for a transaction, but for years. Sometimes forever. As Warren Buffett put it: “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it.”

I won’t stay at a Hilton property for years now. And while I don’t want to create friction for the team I’m working with here in Texas, I hope we collectively move our extensive business — and it is extensive — from this Hilton to literally any other hotel chain.

This is what I call anti-trust — not the legal kind, but the customer kind. The moment trust breaks, the relationship is over. And in an age where every hotel, every rental car company, every airline offers essentially the same product at essentially the same price, trust is the only differentiator.

The Lesson

Sydni and Jason both work service jobs. Both work late nights. Both interact with tired, frustrated travelers.

One of them understood that her job isn’t processing transactions — it’s making humans feel taken care of. The other treated a guest like an inconvenience to be managed.

The difference isn’t training. It’s not pay grade. It’s not experience. It’s empathy. As Maya Angelou said: “People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

Tabitha, Marriott, and SpringHill Suites

I drove five minutes from Home2 Suites to the SpringHill Suites. It was now past 3 AM.

Tabitha was at the front desk. She was happy. Actually happy — at 3 AM.

“If you wait about five minutes, my nightly audit will finish. You can book a room for tomorrow and I’ll give you the room tonight for free.”

We ended up talking while her nightly room audit finished — about customer service, about why it matters, about why some people take jobs they clearly hate and then make it everyone else’s problem. Tabitha didn’t understand it either. Neither do I.

What struck me most is that both Sydni and Tabitha are young — early twenties. And they’re not outliers. I’ve been pleasantly surprised by this younger generation of Americans working in customer service. For the most part, they seem to genuinely get it.

There may be reasons for this. Deloitte’s 2025 Global Gen Z and Millennial Survey found that Gen Z workers actively prioritize developing soft skills like empathy and leadership alongside technical abilities. YouGov research shows Gen Z values honesty, trustworthiness, and authenticity in brands more than any prior generation — and when you value those things as a consumer, you tend to deliver them as an employee. Ipsos data confirms that Millennials and Gen Z are more inclined to seek brands reflecting their personal values, even if it means spending more.

They grew up as digital natives, rating and being rated. They understand intuitively what older generations had to learn: every interaction is public. Every experience gets reviewed. Reputation is everything.

And increasingly, companies are catching on too. Forrester Research found that companies prioritizing customer experience generate 5.7 times more revenue than their less customer-centric counterparts. Their data also shows that improving CX by just one point can increase revenue by $1 billion for a large company. Companies that prioritize employee experience alongside customer experience report 1.8x higher revenue growth. The math is clear: investing in people isn’t soft — it’s the hardest ROI in business.

The Lesson

Tonight was an interesting journey. Three customer service interactions in three hours. Three completely different experiences.

Sydni made me feel like the most important customer in the airport at 1:17 AM on a Tuesday. Jason made me feel like a criminal in a hotel lobby. Tabitha made me feel like a friend checking in at 3 AM.

People are people. But some people understand what that means, and some don’t.

In a world where AI is commoditizing products, where price competition is suicide, and where software can be replicated in a weekend — the Sydnis and Tabithas of the world are your only competitive advantage.

Hire them. Celebrate them. Build your company around them.

And the Jasons? They’re not just bad employees. They’re existential threats to your business. Every interaction like mine doesn’t just lose one customer — it loses every customer that customer would have referred, every dollar they would have spent, every chance you had to compound trust over time.

Fred Reichheld, the creator of NPS, wrote in The Ultimate Question: “The program isn’t about the program. It’s about earning the enthusiastic loyalty of your employees and customers.”

People are people. Treat them accordingly.